Table of Contents

ToggleAccording to the World Health Organisation (WHO), about 15% of the global population has a disability, out of which 80% of them live in countries in the South1. As per our latest Census, the 2011 Census, the number of persons with disability (PWD) in India was approximately 2.21 Crore2. The numbers from the Census indicated that disability was significant in our social structure. Therefore, we needed a legislation which would respond to the socio-economic challenges faced by the PWD and create a more inclusive society where individuals with disabilities are integrated into the society rather than being marginalised. Earlier, India followed the Persons with Disability (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995 (PWD Act). But after India ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), it realised the need for a legislation at par with the international convention, thus resulting in the passing of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (RPWD Act) which replaced the PWD Act. We will understand the history of the RPWD Act, 2016 along with the changes from the PWD Act and the rights laid down in the 2016 Act, which is the current legislation.

Until the 1970’s, in India persons with disability were treated as outcasts and they faced injustice all the time. But in contrast to the situation in India, the Western disability rights movement (DRM) gained prominence, primarily because after World War II, many soldiers returned home with several disabilities, thus becoming the initial source of the DRM. Their rights saw some success because they were considered heroes, therefore they were supported by the public immensely.

In the 1970’s, India had not yet begun to recognise the rights of PWD. Throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s, the DRM remained a struggle between only a couple of individuals and the system. Not everyone fought for their rights out of fear of being treated as outcasts, since even family members of the PWD experienced stigma by association and were looked down upon. Any form of assistance given to the disabled population was seen as charity rather than giving legitimate rights to the PWD. But activists like Baba Amte, began to raise awareness and sensitized people towards the cause of fighting for the rights of PWD.

After being inspired from prominent social activists like Baba Amte, people realised the importance and started joining hands with the DRM. The 1980’s saw a shift from a Welfare model to a Developmental model wherein PWD who were previously treated as recipients of charity were now part of a developmental process. By the end of 1980’s, people focused on the PWD from a medical perspective, by assisting with medical treatments and technical equipment. The United Nations (UN) declared 1982-1993 as The Decade of Disabled Persons3, which prompted India to establish the Rehabilitation Council of India in 1986, followed by the Mental Health Act, 1987.

During the 80’s and 90’s, several NGOs came up and they collectively brought in different ideas and consolidated demands regarding accessibility and rights of the PWD. This was followed with a series of protests and petitions, which resulted in the Government passing the PWD Act, 1995. Through this Act, a PWD category with 3% reservation was made in all government posts. Thus, in 1995, PWD gained recognition and inclusion in education and government sectors.

On 1st October, 2007, India ratified the UNCRPD, which placed emphasis on dignity and recognised that disability while being an evolving concept, results from “interactions between persons with impairment and the attitudinal and environmental barriers” that impede their participation in society. This focus called for reflection on psychosocial and environmental barriers and the role they play in limiting functioning and disabling folx when working on affirmative action.

The RPWD Act, 2016 was passed in alignment with the Convention, and encompasses various spheres – educational, social, economic, legal, political and cultural. The RPWD Act incorporates a rights-based approach – a step up from the previous 1995 Act, which promised reservation, education, rehabilitation programmes etc. for persons with disability, holding a charitable stance.

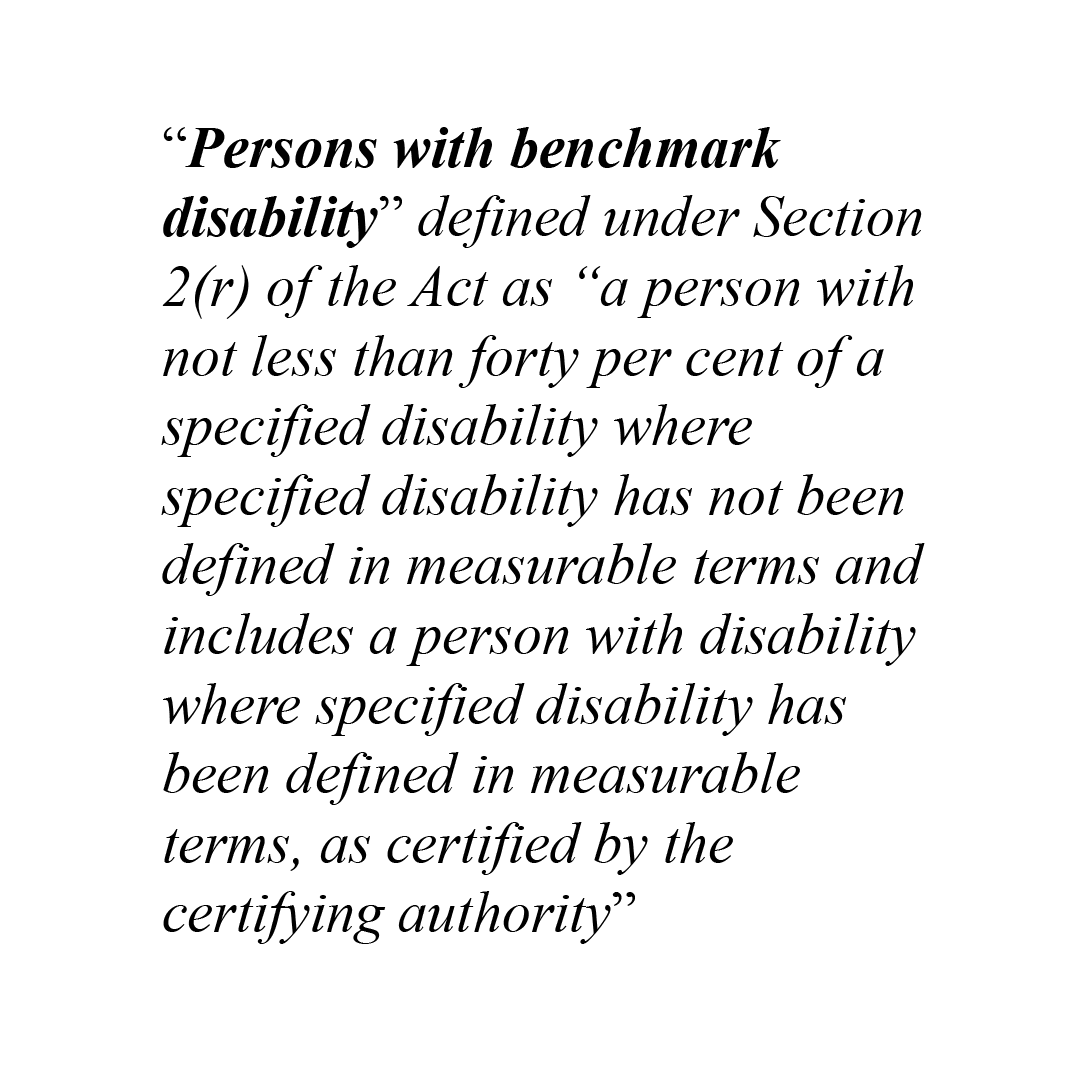

The Preamble of the 2016 RPWD Act aims to uphold the dignity of every PWD in the society, prevent any sort of discrimination against them and protect them from discrimination. The Act also includes certain definitions that were not there in the previous Act such as person with benchmark disability, care giver, discrimination and high support.

Some of the major shifts from the PWD act, 1995 to the RPWD Act, 2016 are: –

There are certain rights and entitlements of persons with disability are mentioned in Chapter II of the Act, from section 3 to section 15. With the shift from the PWD Act 1995 to the RPWD Act 2016 there have been several rights which are now recognised by the current Act. The RPWD Act explicitly states’ rights with regard to legal capacity, reproduction, voting, guardianship and justice. The provisions are: –

Some of the rights guaranteed to persons with benchmark disability are:

1. Providing free books, learning materials and appropriate assistive devices to children with benchmark disabilities until 18 years

(Sec. 17)

2. Right to free education between 6-18 years (Sec. 31)

3. 5% reservation in higher educational institutions (Sec. 32)

4. 4% reservation of all job openings in each group of posts in Government offices (Sec. 34)

5. Special schemes shall be made by the appropriate government authorities (Sec. 37)

6. High support may be provided if required (Sec. 38)

The article gives the readers a brief of the historical aspect of the Act and of certain rights and entitlements provided by the RPWD Act 2016. After the ratification of the UN Convention on Disability Rights, our country has progressed by making few major shifts from the 1995 Act to the 2016 Act. Now the rights-based approach is the aim and purpose of the Act. The Act has been made more inclusive by addressing a greater number of disabilities, providing redressal mechanisms and stringent penalties for offences committed against PWD and improving the accessibility factor across various sectors.

While the enactment of the RPWD Act, 2016 marks a significant step towards societal growth, it becomes imperative to see to the implementation of the Act in various sectors, which would result in a healthy and inclusive society for everyone to live in. In our next article, we will explore the role of diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging (DEIB) from an organisations’ perspective, providing the compliance measures and the consequences of non-compliance of the same.

Written by: Kanika Shenoy, Reviewed by Deeksha Rai and Rosanna Rodrigues

1 World Health Organization, Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities. World Health Organization, “Disability”.

2 Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India, Measurement of Disability through Census: National Experiences: INDIA (2011), available at CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 DATA ON DISABILITY

3 United Nations| Dept. of economic and social affairs, available at History of United Nations and Persons with Disabilities – United Nations Decade of Disabled Persons: 1983 – 1992 | United Nations Enable

4 Persons with disabilities Act, 1995, No. 1 of 1996, S.2(s). “Person with disability”

5 Persons with disabilities Act, 1995, No. 1 of 1996, S.2(q). “Mental illness”

6 Rights of Persons with disabilities Act, No. 49 of 2016, S.(zc), “Specified disability” as mentioned in the Schedule.

IAW resources

Browse our help directory